How to Become a Fingerprint Analyst

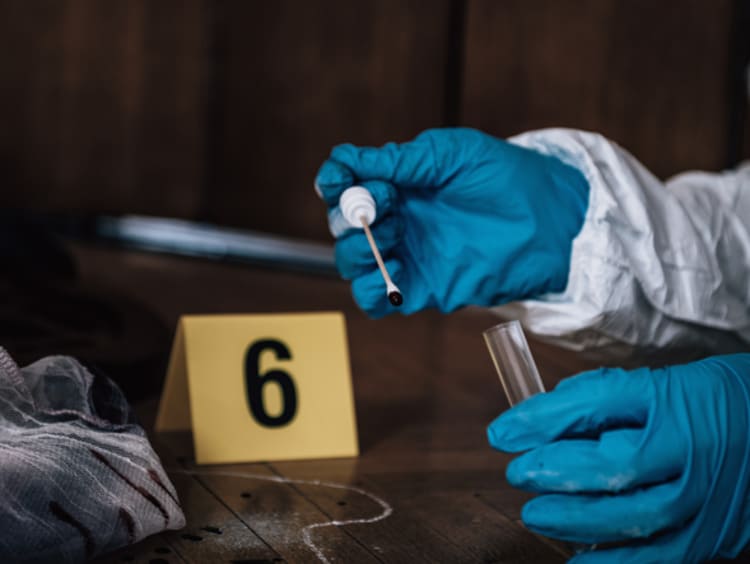

Fingerprint analysts are forensic science technicians who specialize in the identification of fingerprints. They are typically responsible for finding fingerprints at crime scenes, preserving them, testing them in the lab and verifying the identification results. The work of fingerprint analysts plays a crucial role in identifying suspects, solving crimes and convicting criminals. In short, these professionals help to keep their communities safer. If this kind of work appeals to you, consider earning an undergraduate degree that prepares you for it.

In This Blog:

- Understanding Fingerprint Analysis

- Cultivating the Skills for Success as a Fingerprint Analyst

- Earning the Right Degree to Prepare You

- Undergoing Advanced Training

- Acquiring Professional Certification

Understanding Fingerprint Analysis

Before fingerprint analysis became an established science, law enforcement officers had no reliable, scientific way of identifying people. It was relatively easy for criminals to change their appearance and their name to escape detection.

That changed when Sir Francis Galton, a brilliant anthropologist and a cousin of Charles Darwin, determined that no two fingerprints are alike. He also discovered that people's fingerprints remain unchanged throughout their lives. He carefully documented the characteristics of fingerprints: loops, whorls and arches. In 1892, Galton published his fingerprint classification system, which is still in use today.1

Shortly after Galton’s classification system was published, law enforcement officials around the world began using it to create databases of criminals and suspects. In 1910 in Illinois, Thomas Jennings was arrested and convicted for the murder of Clarence Hiller after his fingerprints were detected at the scene. That was the first murder case in which fingerprint evidence was successfully used in the United States.2

Cultivating the Skills for Success as a Fingerprint Analyst

Print analysis can be exciting work, although students should not expect it to be like forensic science dramatizations on popular TV shows. This work is also highly meaningful. Professional analysts have the satisfaction of knowing that what they do helps bring about justice for victims and keeps communities safer. One way to determine whether this career path is right for you is to consider the following characteristics and competencies essential for effective analysts:

- Patience: This line of work involves long hours of sitting at a desk. Expect to spend much of your time looking at computer screens and studying fingerprint cards.

- Attention to detail: Effective analysts must pay careful attention to even the smallest of details.

- Computer literacy: Analysts should have basic computer literacy skills, including the ability to learn new programs.

- Communication: Much of the work that an analyst does is solitary, but it is necessary to collaborate effectively with colleagues and other professionals. In addition, print analysts are often called upon to testify in court about their findings and methods.

All these skills can be cultivated over time, particularly as you work toward your degree.

Earning the Right Degree to Prepare You

The first step toward becoming a fingerprint analyst is to earn an appropriate degree. Most aspiring fingerprint analysts earn bachelor’s degrees in subjects such as forensic science, criminal justice, chemistry or biology. Of all these degree options, forensic science is the most relevant for this particular career path and offers the most comprehensive background for it.

The average forensic science program will cover topics such as:

- Anatomy and physiology

- Forensic scene processing and reconstruction

- Physical evidence analysis

- Instrumental analysis

- Toxicology

- Body fluid and DNA analysis

In addition to these criminalistics-specific courses, students can also expect to study sciences such as general biology, molecular and cellular biology, chemistry and general physics.

Undergoing Advanced Training

An appropriate undergraduate degree will lay the groundwork for pursuing a career as a fingerprint analyst. However, most employers require additional training that is more specific to print analysis. Look for course options at law enforcement and forensics academies or certificate programs from postsecondary institutions.

In some cases, an employer will ask a job applicant to complete a specific course. Popular courses include those offered by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI, for example, offers courses such as “Advanced Comparison for Tenprint Examiners” and “Scientific Basics of Fingerprints: Classifying, Recording and Comparing including the Scientific Basics of Palm Prints.”

Acquiring Professional Certification

Although not all employers require it, you may wish to pursue professional certification after completing your advanced training courses. Even if you land a job without a professional certification, earning this credential may help you pursue higher-level positions within your organization. Furthermore, some employers may fund employees’ certification efforts.

The International Association for Identification (IAI) is one professional organization that offers certification options for fingerprint analysts. This certifying body offers two print-specific credentials: Tenprint Fingerprint Certification and Latent Print Certification.

You can begin working toward this cutting-edge career when you earn a preparatory degree at Grand Canyon University. Apply to enroll in the Bachelor of Science in Forensic Science program and emerge with foundational knowledge and skills in biochemistry, pathophysiology, physical evidence analysis, crime scene processing and much more. Click on Request Info at the top of your screen to learn more about joining our supportive learning community.

1 Retrieved from FindLaw, Fingerprints: The First ID, in March 2021.

2 Retrieved from Smithsonian Magazine, The First Criminal Trial That Used Fingerprints as Evidence, in March 2021.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Grand Canyon University. Any sources cited were accurate as of the publish date.